Billions of people rely on maps to safely and efficiently navigate our world. Maps aren’t food, clothing or shelter, but they’re about as close to a basic human need as you can get. As we move from destination to destination, we trust our navigation devices to chart the best course. Next to our eyes, our phones and GPS systems provide the clearest view of our world.

Naturally, we want the maps we rely on to be accurate. But do they always present the most truthful representation?

This op-ed is part of CoinDesk’s new DePIN Vertical, covering the emerging industry of decentralized physical infrastructure.

No, not always. And this poses a significant issue.

Modern maps are data repositories, navigation systems and marketing devices. In their digital form, maps do much more than just offer a snapshot of the world. Our society has grown increasingly reliant on maps to source everyday information. According to Google, more than 1 billion people use Google Maps each month. Likewise, a UnitedTires study revealed that 60% of American drivers use a GPS service at least once a week. Combined with on-demand delivery, taxi services, and searches for points of interest (POI) such as restaurants, supermarkets, and charging stations, maps impact most people on a near-daily basis.

So, who decides what data gets included in a map? What information is omitted? Is our navigation taking us down the best path? Who draws the lines?

To answer these questions, we must look at leading mapmakers and their motivations for shaping our world. As maps become more prominent in our lives, these map makers hold significant influence over day-to-day decisions. However, few alternatives exist for people to access accurate map data as a public good. Hence, the case for decentralized and open-source projects to overcome the siloed and gatekept mapping ecosystem.

Today, a select group of cartography companies are responsible for creating and maintaining the majority of mainstream digital maps.

Each map conveys a particular viewpoint shaped by its creators. Plotting points and drawing boundaries may seem straightforward, but these tasks involve numerous choices and inherent biases.

Maps can drive behavior, and creators of purpose-built maps might downplay or elevate features to create desired outcomes. For example, a restaurant may sponsor a navigation feature that shows their destination as “recommended” despite distance, star rating and so on. In this case, the map forms a pay-to-play ecosystem where businesses that “sponsor” dominate navigation and traffic, despite not necessarily being the “best” option.

Monetizing a map is not itself a malicious act, but it does carry significant consequences if the only free-to-use consumer products are primarily directed by ad spend. On the other hand, map companies must generate revenue to sustain map data collection and innovation. As a result, most public consumer maps make trade-offs between corporate suggestions and data freshness and accuracy.

On the business-to-business side, map companies rely on proprietary information to remain competitive. Therefore, free-to-access maps are rarely as dynamic, fresh, and data-rich as they could be.

When it comes to publicly available map environments, most of us make do with the few free map sources at hand. These maps are generally operated by large entities that have long dominated internet search and discovery. While they continue to update maps and roll out new features, their priorities and motivations aren’t always aligned with the public’s interests.

A recent X post by a former Senior UX Researcher for Google Maps, Kasey Klimes, highlighted this issue. Klimes explains the internal rationale behind Google Maps not including “scenic” or “safe” navigation options. The thread, which has since amassed millions of views, is filled with critics questioning the company’s motivations for omitting these highly requested features.

The decisions made by cartographers reflect their understanding and the data they have. Most maps today are not a singular perspective but rather a patchwork of data from “trusted sources.” While map companies can cross-reference sources to improve accuracy, it’s an imperfect system.

Despite their best efforts, mapping companies have faced significant challenges in verifying the truth and accuracy of their data. Geographic disputes, censorship, accidental additions/omissions, and bad actors seeking financial or political gain all present opportunities for data corruption.

For example:

In 2019, Google Maps faced a major issue when the Wall Street Journal discovered millions of false business addresses misleading the algorithm that suggests local service providers.

The Chinese Ministry of Natural Resources caused international outrage when their “standard map” expanded the country’s borders into contested areas, prompting objections from the Philippines, Malaysia, Vietnam, Taiwan, and India.

Baidu and Alibaba’s digital maps recently came under fire for failing to correctly demarcate Israel as a country.

In 2019, the U.S. military warned of an increased risk of deep fake satellite images and location spoofing used to create tactical advantages in conflict zones.

In 2016, Google began broadcasting “Government Requests,” revealing thousands of censorship petitions in just six months.

The long-held practice of including trap streets (invented or distorted map features to prevent plagiarism) has led to several accidental map misprints over the years.

We’d like to believe that most map companies would never intentionally mislead the public, but it’s naive to think that external sources and authorities might not exert control over map entities. Mark Monmonier said it best in his book How to Lie with Maps: “Because most map users willingly tolerate white lies on maps, it’s not difficult for maps to also tell more serious lies.”

Blindly trusting a single source of information is a recipe for disaster. As technology creates more sophisticated ways for compromised data sets to infiltrate map providers, companies are looking for better, more efficient ways to verify information at scale.

In 2004, OpenStreetMap (OSM) proposed the first major open-source solution to the map-making bias problem. It relied on the collective intelligence of global volunteers plotting geospatial data for anyone to use and reference.

OSM has been a significant step in the right direction for mapping. Hivemapper and almost every other cartography agency enthusiastically support and use the OSM database to create mapping foundations. As an open initiative, OSM doesn’t house any overt bias and allows the entire network to determine what is true and accurate.

However, it is not without its issues. Lacking direct incentives or remuneration for independent contributors, the OSM platform today runs mostly on old or donated imagery from major corporations. While the system remains open for edits, buffering against blatant corruption of geospatial data, OSM still struggles to keep pace with modern cartography efforts.

Read more: Daniel Andrade – DePIN Is the Sharing Economy 2.0

Many errors and biases slip through the cracks, burdening map makers with a constant game of whack-a-mole. Although the solution is more immune to singular manipulation, it is not completely impervious. Cartographic data warfare remains an issue, and independent users can periodically corrupt map information, as seen with the mysterious user editing OSM in China’s favor.

In a perfect world, who would draw the lines? We would — all of us. Not just a select group of cartographers. If given equal opportunity to access fresh and accurate data, we’d throw off the shackles of siloed and gatekept mapping ecosystems and create a complete, fresh, and infinitely customizable map experience.

It all amounts to data.

We have the model for openness from OSM, but it doesn’t overcome the issues of collecting and vetting unbiased data while maintaining a network of valid sources. Unfortunately, human intermediaries are fallible. Middlemen corrupt sources, keep fresh data behind lock and key, and inject maps with their own biases.

But what if the “human” element was minimized? What if we could create a self-regulating map network that only presented honest information? With blockchain technology, this type of map network is no longer a pipe dream.

If we provide everyone with equal access to map data, we disrupt the monopolies that currently dominate the mapping world.

In simple terms, a blockchain is a ledger that accurately tracks contributions to a network. Similarly, cryptocurrencies use smart contracts to automate incentives within that network, proportionally rewarding contributions. These contributions can also extend to primary source hardware, such as dashcams.

Projects like Hivemapper have leveraged blockchain-based rewards to recruit large networks of map data contributors. However, these map contributors do not act as middlemen, nor do they exert bias within the network. Contributions are automated through purpose-built hardware and AI software, programmed to collect raw objective map data.

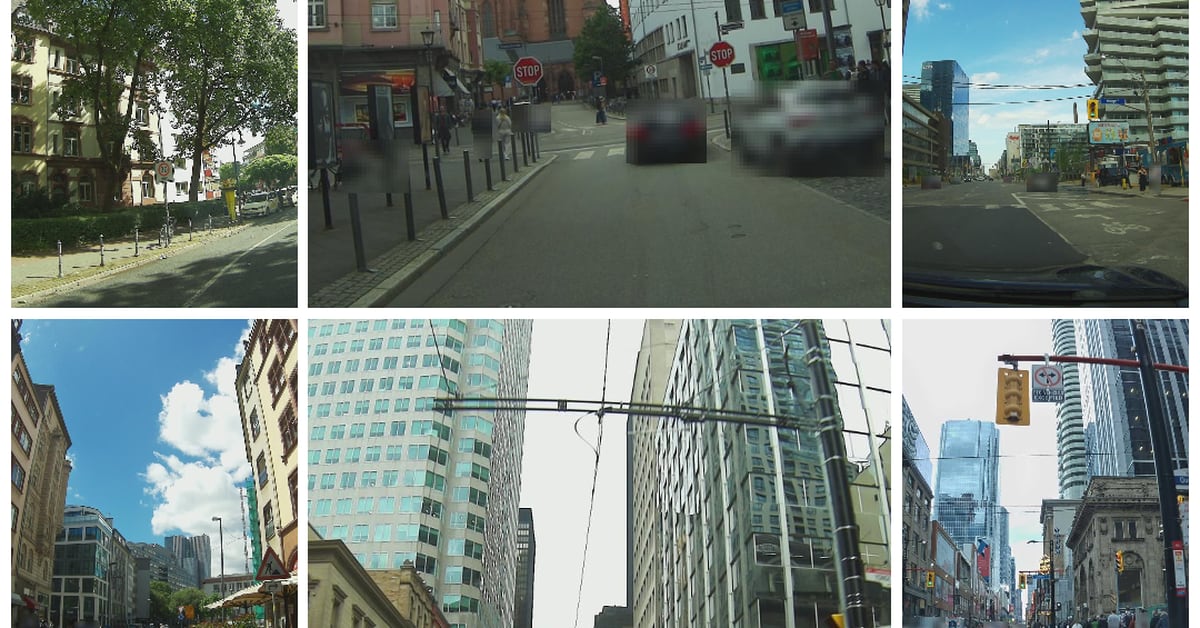

In Hivemapper’s case, contributions are attached to dashcams that capture and vet street-level imagery, and reward camera owners with cryptocurrency. Outside of the initial installation of the camera, human elements are minimized. Instead, the high-definition imagery captured by the dashcams does the heavy lifting of identifying and plotting map features.

Thousands of people drive on roads every day, the very roads we aim to map and analyze. So, naturally, we have map-ready fleets at our disposal. By supplying purpose-built dashcams that double as map-making machines, Hivemapper is able to automate map data collection at a global scale.

Read more: Sean Carey – Every DePIN Has a Story

It’s an unbiased system that cross-validates imagery from multiple drivers and gamifies participation with regional incentives. By minimizing the human element, trust is no longer a factor but rather a variable within the network that is constantly weighed. Any bad actors looking to inject false data into the network are easily identified as other drivers retrace mapped roads and confirm or reject preceding map contributors. Those contributors that provide high-quality data to the network maintain regular rewards. Those that taint the data pool are removed from the network and omitted from the reward cycle.

Yes, people will warp and shape data to meet their desired outcomes. That isn’t something we can change outright. But if we provide everyone with equal access to fresh, accurate, and affordable map data, we disrupt the monopolies that currently dominate the mapping world.

Certain map components are objective, dependent on factual truths. Things like street names, road conditions, and sign locations are rarely the subject of debate. Starting with basic geospatial data, we can create an honest foundation for maps.

From there, users can layer on additional data for navigation, points-of-interest, business needs, etc. Through a decentralized network, we can automate elements of map freshness and, with open APIs, developers can continually innovate and create dynamic filters. Then, the public can access open marketplaces of maps and self-determine which maps best fit their needs.

Note: The views expressed in this column are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of CoinDesk, Inc. or its owners and affiliates.