Decentralization is a central principle of the blockchain and crypto industry, yet its true meaning is often overlooked by most. Today, we take a closer look at the implications of this important term in the context of the blockchain & crypto industry.

What Is the Significance of Decentralization in a System?

Let’s focus on a similarly mis-used term which nonetheless carries significant meaning within the blockchain and crypto industry: decentralization. This buzz word, often carelessly thrown around by developers, advertisers, and the press alike, represents a central concept of the ‘blockchain’ industry, as it is one of the main differences between ‘legacy’ financial system instruments (such as banks) and crypto’s decentralized finance (DeFi).

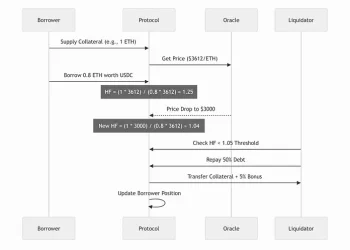

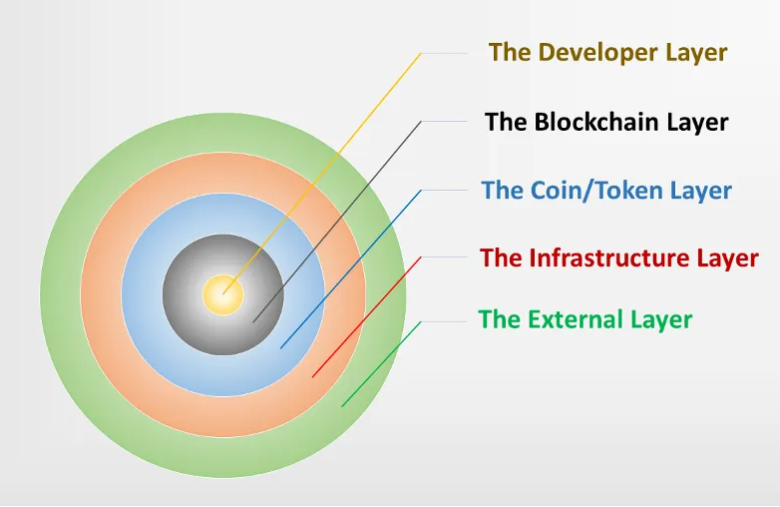

In addition to this, the importance of decentralisation becomes yet more apparent for the crypto industry as it ensures censorship protection: the more decentralized a blockchain is, the fewer points of failure exist within its system, and the more difficult it becomes to control, restrain or shut it down completely. This is particularly relevant in the context of government regulations, which will find it near-impossible to regulate a blockchain which does not possess a centralized, governing company or person. Unfortunately, decentralization is also difficult to fully implement as it often comes at the expense of scalability or security, as is depicted in Vitalik Buterin’s ‘Blockchain Trilemma’.

Source: Vitalik.ca

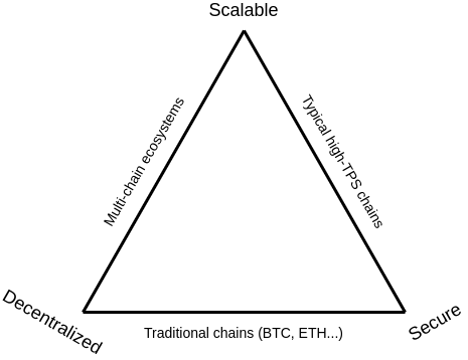

Despite this difficulty, efforts are consistently being deployed across the industry to ensure blockchains continues to strive for greater decentralization. One of the main difficulties with implementing true decentralization is that the system only remains as decentralized as its most centralised link. The ‘links’ here refer to the different operational layers that the system (or ‘blockchain’) consists of, i.e. 1) the developer layer, 2) the blockchain layer, 3) the coin/token layer, 4) the infrastructure layer, and 5) the external layer. The level of decentralization of any blockchain project will rise with increasing number of its layers operating via decentralized processes, however there will always be a ‘single point of failure’ from which the blockchain can be shut down as long as even a single layer continues to operate via centralised structures.

Schematic representation of the different ‘layers’ of blockchain decentralization

The Developer Layer

This layer of operations includes the ‘builders’, i.e. the developers and coders of the project. At this layer, decentralisation means that those involved in building and coding the blockchain/program are numerous and un-affiliated (to a same company or group), ideally spread out over multiple countries across the globe and importantly: with varying levels of responsibility. In such a setup, it would be difficult to stop every developer from working on the project, however in the opposite example (i.e. where most if not all developers work at a company which builds and maintains a blockchain) all it would require would be to stop the company from carrying out its operations (through regulations) and the project would grind to a halt.

For example, in the United States, centralised financial authorities such as the securities and exchange commission (SEC) utilise the Howey test to decide whether certain assets should be classified as securities or not. This is a very hot topic currently in cryptocurrencies and relies on whether the public ‘invests in a company (or its coin/token) with a reasonable expectation of profits to be derived from the efforts of others’. The key terms are highlighted in bold: the more centralised a crypto ‘company’ is, the more the above statement applies to it. This is the case with Ripple (XRP), currently embroiled in a lawsuit against the SEC which has lasted for years, relating to its centralised company structure where the ‘efforts of others’ (read: developers) feed XRP buyers’ ‘expectations of profits’.

The developments of this lawsuit are particularly important for the future of the industry as many crypto companies operate in a centralised manner and could thus become future targets for the SEC’s censorship efforts. This shouldexclude Ethereum however, as ex-chairman of the SEC William Hinman once stated ‘Ethereum is not a security because it is sufficiently decentralised’ though unfortunately, William never stopped to clearly defined what he meant by ‘sufficiently decentralised’, leaving very little clarity on what this actually meant. Furthermore, the SEC chairman has now changed, and William Hinman’s replacement, Gary Gensler, is doing all he can to make this distinction as confusing as possible with the intent of setting a precedent with Ripple to then label many crypto companies and their tokens as securities.

Apart from the problem of regulatory censorship, it is also important to spread out the skills and responsibilities between developers as significant delays could ensue in the event of even a single ‘senior’ developer (in charge of multiple key parts of the project) suddenly becoming unable to work for extended periods of time. Such an eventuality has already taken place in March of this year, with the departure of revered developer Andre Cronje from the Fantom team. Andre was regarded by many as a ‘DeFi guru’ prior to his departure and was in charge of a number of important features within Fantom’s DeFi ecosystem, especially with respect to the management of the total value locked (TVL) of the system. In the weeks that followed Andre’s departure, more than 20 decentralised applications (dApps) were shut down, remaining offline to this day, including Yearn.finance, Solidly, Keep3r network and others. DeFi activities within the Fantom ecosystem significantly wound down as a result, with just under 30% of the system’s TVL disappearing over the same time frame; all attributed to the departure of just a handful of developers, though mainly Andre Cronje.

Source: web3wire.news

The Blockchain Layer

This represents the most widely recognised layer when colloquially discussing the ‘decentralisation’ of a blockchain, and most often relates to the blockchain itself, i.e. its full transaction history, the nodes and/or validators of that blockchain, and where each are located. Most news outlets often refer to the number of validators of a blockchain as a single measure allowing for the assessment of how decentralised a blockchain is, however this is a simplified view which can often obscure the real question. For example: in many blockchains, such as Algorand and Solana which in both cases boast over 1000 validators, transactions are actually processed via smaller clusters of 120 and 150 validators respectively. These validators are either associated or entirely run by Algorand- or Solana-associated entities.

This measure of decentralization becomes even more irrelevant when one considers the fact that most (if not all) cryptocurrency projects utilise centralised cloud computing services, such as Amazon Web Services (AWS), Google Cloud (GC) or Azure Cloud Computing, to run their blockchain. This is tantamount to encasing a decentralised blockchain within a centralised coffer or safe: whoever owns the key to the safe (i.e. who is in charge of the centralised cloud computing service) can dictate when the blockchain goes online and when it gets shut down. This is a major point of failure, as was the case for the decentralised exchange (DEX) dYdX in December 2021, when AWS had another outage causing the DEX to go offline for the second time that year. Many projects are attempting to find solutions to this problem, notably with Near Protocol which is attempting to split its validators between different cloud computing services.

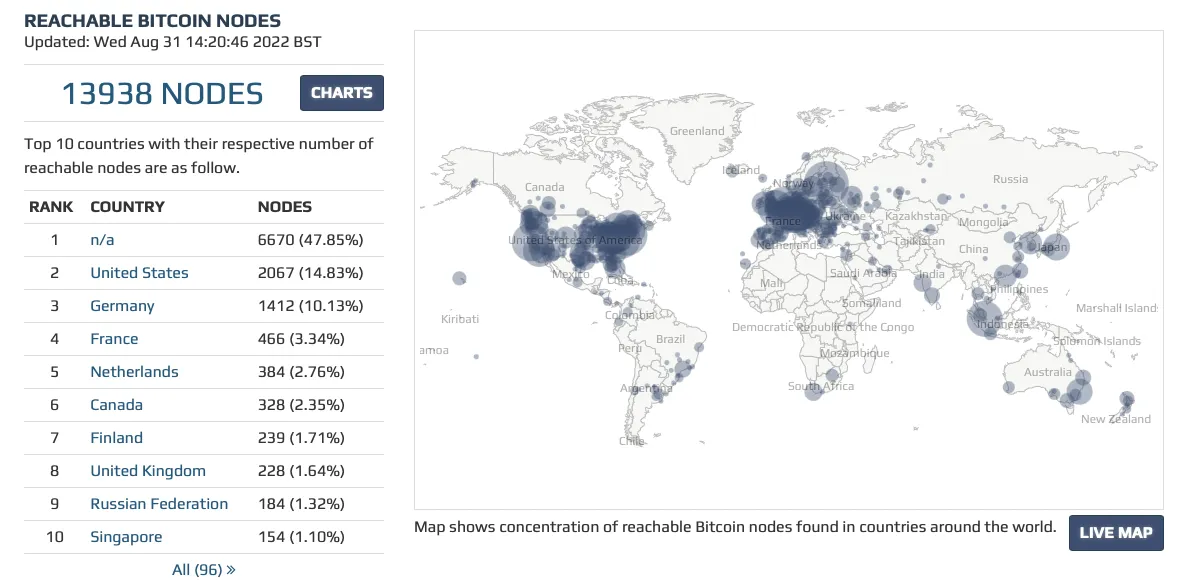

Further worsening this problem, blockchains don’t just run their operations with cloud computing services but also employ such services to store their full transaction history, increasing centralisation. Bitcoin is the most decentralised of all cryptocurrencies in this respect, as transactions are validated by over 14,000 nodes spread out across the world who each store the full Bitcoin transaction history on their own devices.

Quantification of Bitcoin full nodes around the world, including country break down.

Source: Bitnodes.io

The Coin/Token Layer

This layer refers to the distribution of coins or tokens amongst holders and is possibly the layer with the highest variability in level of decentralisation across different cryptos. This is because with relatively low liquidity still for most cryptos (compared to legacy banking asset classes), a whale who owns over 50% of a crypto’s tokens can manipulate the price by dumping some of its tokens on the open market. Price manipulation is a major concern in cryptocurrency markets and can still be achieved even for coins which enjoy a higher level of liquidity (including ETH and BTC) with the coordinated dumping of coins by several whales. Problems caused by the centralised ownership of most of a blockchain’s coins is made worse when considering the impact this can have on governance voting of decentralised autonomous organisations (DAOs).

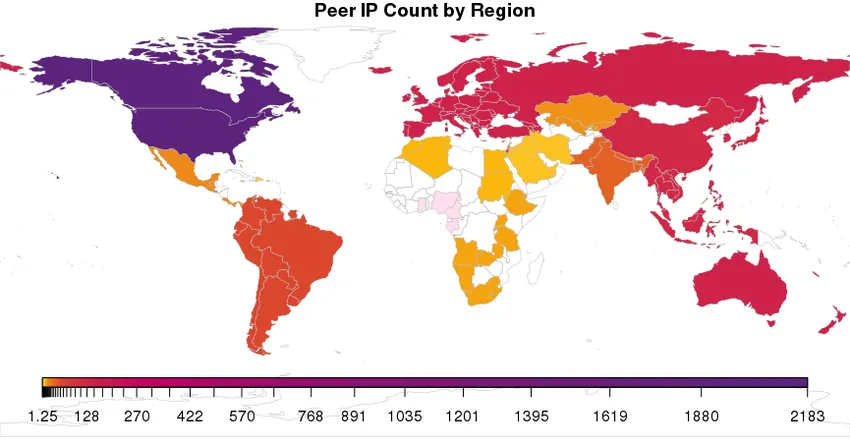

Country-specific distribution of Ethereum-bearing wallets (ETH) throughout the World.

Source: ResearchGate.

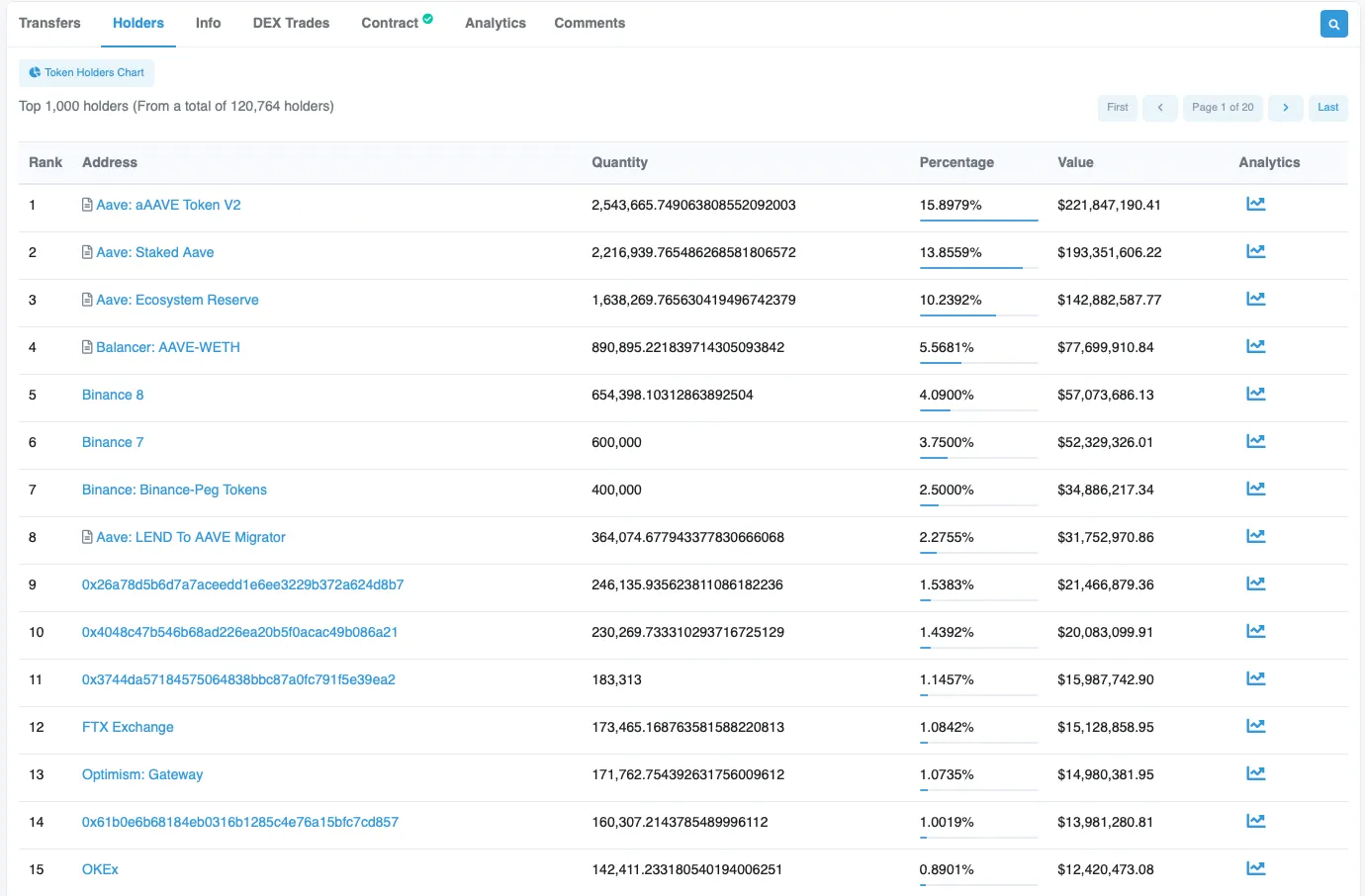

This is a major topic which would honestly require its own full article (which we will focus more on in the coming weeks) however it can be simply stated here that for blockchains which also use their tokens for governance voting (i.e. that are also used to submit proposals and cast votes within their DAO protocol), a whale can use their disproportionate amount of tokens to sway the result of votes one way or another. This is most often the case for centralised exchanges like Binance, Coinbase, KuCoin and the likes, who often own significant percentages of different crypto tokens from DeFi protocols (i.e. their token trading liquidity pools) and who can often use those to sway governance votes in a manner that interests them (big corporations) rather than retail investors. This is the definition of an unfair system where users therefore have to contend with a ‘rigged’ system where their vote does not really matter — akin to current real-life systems in other words. Such problems were seen with Uniswap both in 2020 and 2021, where proposals were passed by a couple of whales against the will of hundreds of small voters.

List of top 15 AAVE token holders: includes major centralised exchanges like Binance (10%), FTX (1.1%) and OKEx (0.9%) major DeFi liquidity providers like Balancer (5.6%) and AAVE (42%) themselves, as well as layer 2 scaling solution Optimism (1%). Together, the top 15 AAVE holders possess just under 67% of all AAVE tokens currently in circulation.

Source: Etherscan.io

The Infrastructure Layer

Decentralisation at the infrastructure layer refers to the range of different programs and technologies that are used to access blockchains. The first technology that comes to mind are the different wallets used to transfer coins to, from and within blockchain ecosystems, such as Metamask for the Ethereum blockchain. The problem here is akin to previous ones we have seen where centralised companies are in charge of handling blockchain-critical services/actions. These centralised companies represent single points of failure, which can be actioned either from actors outside of the direct blockchain industry (government and regulators ordering their operations be halted) or as a result of outages from companies which provide services on which these wallets rely to operate correctly.

This was the case with Infura, a service provider Metamask uses to access the Ethereum blockchain. Every time Infura has an outage (which has now occurred twice), several features within the Ethereum blockchain usually also go offline, including the ability for Metamask to operate transactions. Furthermore, Metamask can be ordered by regulatory bodies to cut service to users from specific countries, essentially locking users out of their Metamask wallets within the targeted countries.

Similarly, centralised exchanges represent the main vector through which users can exchange fiat for cryptocurrency, thereby representing a major infrastructure within cryptocurrency markets. Again, centralised exchanges have the quality in their name: they are centralised and can therefore either be censored by overbearing regulation, shut-down due to inadequate risk mismanagement and insolvency, or suffer outages due to service provider outages. Yet interestingly, centralised exchanges didn’t use to be this ‘centralised’: back even just a few years, exchanges were actually quite decentralised by virtue of their lack of physical offices or headquarters, while their company umbrella often consisted of multiple subsidiaries registered in countries with little to no crypto regulation.

Making the case for their decentralisation even stronger: the teams of people who would work for such exchanges were often also decentralised, as the lack of offices meant a lot of these people, machines and services worked and operated from dispersed locations around the world. This however is not the case anymore, with the implementation of tougher regulations over the past 2 to 3 years which has seen many ‘rogue’ centralised exchanges either abide to new regulation (such as requiring to register with central authorities and implement KYC and AML with their users) or get shut down entirely.

The External Layer

The fifth and final layer of decentralisation is the external layer, i.e. anything that the cryptocurrency industry relies on that isn’t ‘strictly cryptocurrency’. Sadly, and as a word of warning, most (if not all) cryptocurrencies fail at this level of decentralisation, as it would otherwise require that real-world companies the blockchain industry uses to exist to themselves be decentralised first. The external layer can include websites, internet service providers (ISPs), hardware and financial institutions (banks). Firstly, websites and ISPs are all centralised companies which, as we have discussed several times, can be coerced, or censored by regulatory bodies/governments. But importantly, most (if not all) websites for DeFi protocols across all blockchain ecosystems are hosted on centralised servers and cloud computing services and can therefore be shut down by these internet and cloud services, whether this request comes from these centralised corporations, or governments.

ISPs could similarly be ordered to stop serving crypto-related websites in places like India, who have imposed blanket bans on cryptocurrency. An example of this is Uniswap (once again), which was forced to delist dozens of tokens from its front end in such a manner. A possible solution to this may come from blockchain project Helium, which is attempting to build a decentralised version of the internet, where such censorship could not take place.

Hardware can also represent a vector for centralisation if, for example, the hardware required to validate transactions on a blockchain is only available from a couple companies worldwide, or if the price becomes exorbitant, such as with the CPUs required to mine Bitcoin. The increasing price of the hardware, as well as the rising price of energy and lower price of BTC means that over the past 6 months, small miners are being priced out while larger mining corporations have been hit less hard thanks to their economies of scale.

Finally, there are institutions, referring mostly to the availability of stable coins. We recently posted an article going into more depth with respect to the technology behind stable coins and all the freedom such tokens have allowed in cryptocurrency markets, to the point where stable coins back most cryptocurrency assets and form the bedrock on which the crypto industry relies. Yet the problem is (at least for fiat-backed stable coins, which also represent the largest issuers such as Tether and Circle) that these centralised companies hold their reserves within financial institutions such as banks. No introduction is required here: it is a risky plan to leave one’s crypto-related fiat capital in a class of institutions notoriously averse to cryptocurrency activities, as most banks are. Banks can compromise access to such reserves, which would deny stable coin issuers from being able to access these funds when required. Such an event would spell disaster within the industry, even if only for a few hours.

In Which Cryptocurrencies Is Decentralization Most Evident?

It will come as no surprise to many that the most decentralized of all cryptocurrencies today is Bitcoin. That is because the supply of Bitcoins is broadly distributed (developer layer), there are dozens of institutions and individuals coding and building on Bitcoin from locations around the world (coin/token layer), and for which there is therefore ample infrastructure including wallets, and the fact BTC is basically the ‘base’ currency within the crypto world (infrastructure layer). As discussed above, the Bitcoin network is also supported by close to 14,000 full nodes who each store their own copies of Bitcoin’s full transaction history (blockchain layer), while Bitcoin is still lacking decentralization in its external layer, though that is where all cryptocurrencies stumble still, as it requires external businesses to go down the route of decentralization first. In fact, no other cryptocurrency even comes close to the decentralization already achieved by Bitcoin.

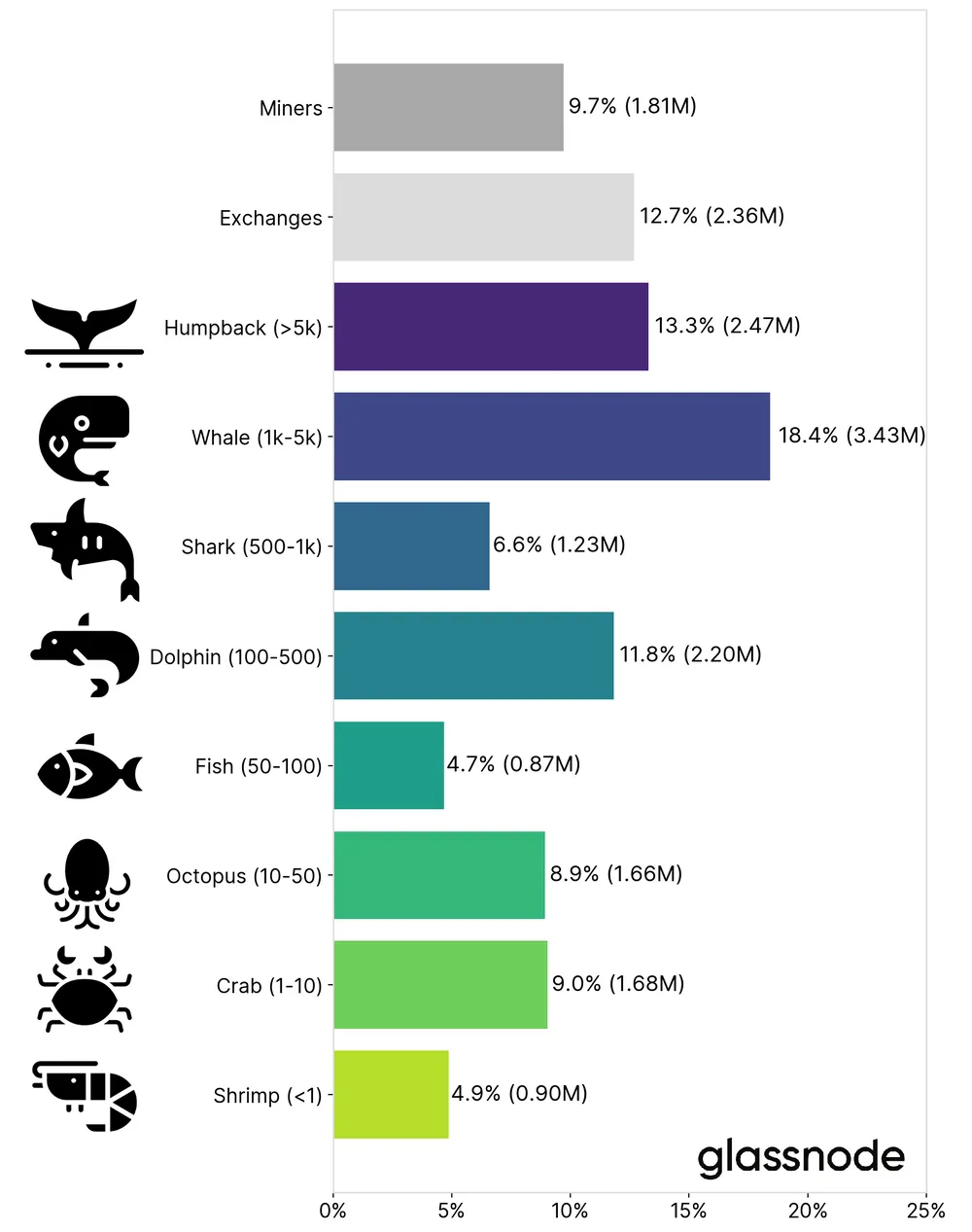

Distribution of Bitcoin tokens among holder type, by wallet size.

Source: Glassnode.

So, which cryptos come next? Well, Ethereum, Monero and Litecoin must be mentioned here, as they are all actively being built by developers who are also spread around the world, their tokens are well distributed though Ethereum lacks some decentralization on its blockchain and external layer (mostly due to reliance on cloud computing services) while Monero is constantly at risk of getting delisted from centralized exchanges (infrastructure layer) due to its privacy features. Litecoin also enjoys a wide developer base spread across the world, however, it suffers from a more centralized pool of miners than Bitcoin (blockchain layer).

Taken together, it is interesting to realize that the most decentralized cryptocurrencies are also some of the oldest cryptos to have been created. This may suggest achieving true decentralization doesn’t just take smart planning, but also time. Indeed, in a world that has not broadly adopted decentralization yet, it may take significant efforts to ensure one’s own processes and technology practice full decentralization; with most cryptocurrencies currently striving for this same objective over the coming years, the possibility of achieving satisfactory levels of decentralization remains an attainable goal for most cryptocurrencies.

Future developments Towards Greater Centralisation

The low-hanging fruit in the long list of developments and changes needed to make the crypto and blockchain industry truly decentralised is the mass adoption of decentralised storage. This would have significant impact on many aspects of the infrastructure and blockchain layers, as the former includes most (if not all) Web3 websites currently being stored on centralised servers, while the latter includes full transaction history of different blockchains being stored on centralised storage in addition to running blockchain processes with the help of cloud computing companies (such as AWS). Solutions such as Arweave and Filecoin could fill this technological gap.

Similarly, the development of a reliable and decentralised, peer-to-peer internet would provide significant advancement for the decentralisation of cryptocurrencies as a whole, as such a move would take the power out of the hands of ISPs who would no longer be able to restrict access to crypto-related websites or allow for the introduction of country-wide censorship. Helium and others such as Zeronet or Freenet are companies that are working towards the development of a decentralised and permissionless web. As one may notice, both of the above-mentioned points require for currently (mostly) centralised networks and companies to change their processes to others which rely on decentralisation. This is a recurring theme when discussing the requirements for a truly decentralised crypto industry, and hints at where the future of innovation may lie for the tech industry as a whole.